Women often don't think they are capable of launching their own businesses, which is one reason there are significantly fewer female entrepreneurs than male entrepreneurs, according to the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2012 Women's Report released today.

What's more, women report being generally more afraid of failure than their male counterparts, according to the research, jointly sponsored by Babson College in the U.S., Universidad Del Desarrollo in Chile, and the University Tun Abdul Razak in Malaysia. The 2012 GEM survey, the 14th of its kind, surveyed 198,000 people in 69 countries. The GEM Women's Report looked at 67 of those economies.

In all but seven of the countries surveyed, women represent a minority of the nation's entrepreneurs. The seven economies where there are as many or more women as men entrepreneurs are Panama, Thailand, Ghana, Ecuador, Nigeria, Mexico and Uganda, the report says.

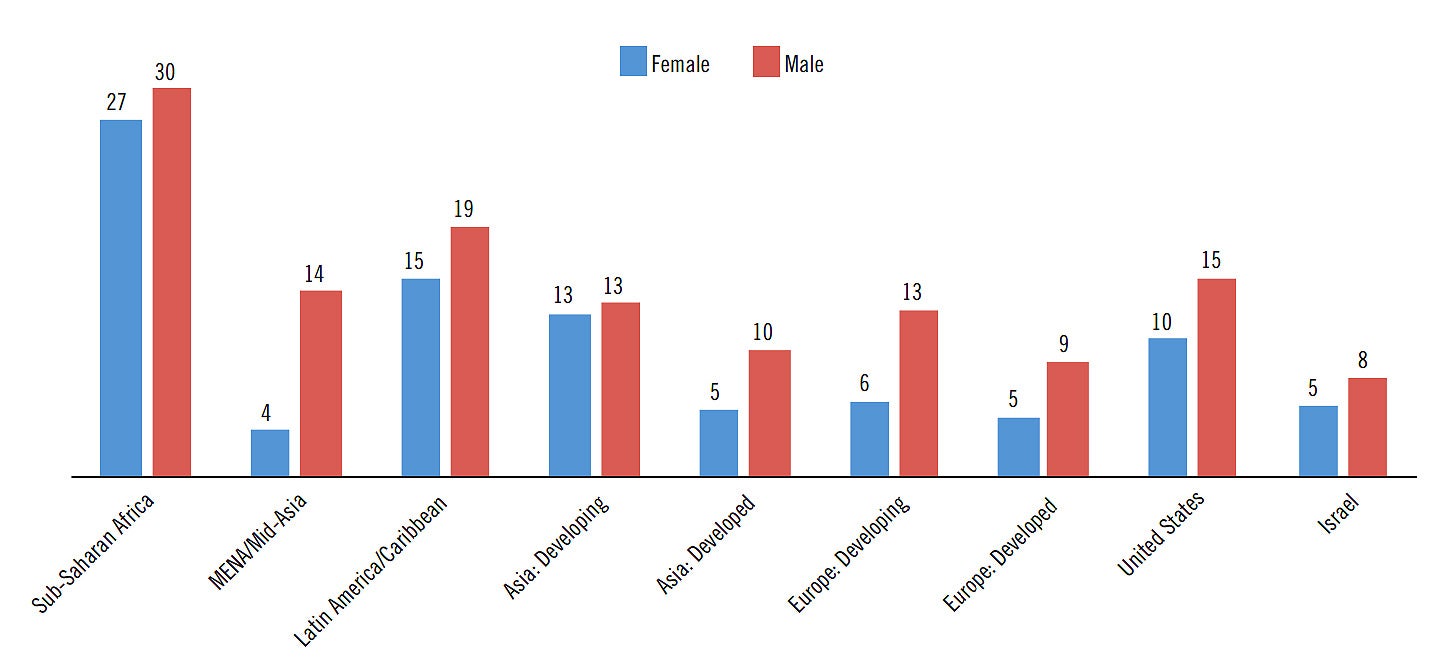

Comparison of female and male total entrepreneurship activity rates by region.

Click to Enlarge+

Source: Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, 2012

To be sure, cultural expectations of women affect the likelihood that they will start a business. For example, in Chile, women are largely expected to take care of their children and parents, making it much harder for women to take an active role in running a business, the report notes. Moreover, many nations have longstanding cultural traditions that both discourage women from working outside the home and from taking leadership positions. In the Republic of Korea, for instance, women face significant hurdles in breaking into what is a very male-dominated business culture.

In the U.S., there are fewer overt barriers for women to become entrepreneurs, but there are still "covert" barriers, the report says, specifically in gaining access to capital or winning government contracts. "These covert practices are subtle, and sometimes not even recognized by entrepreneurs, in that they have to do with status expectations or gendered roles," the report says.

One classic example is the expectation in the U.S that venture capitalists will be men, the report notes. Lead author of the study and Babson professor Donna Kelley points to studies that show women are less likely to receive venture capital funding. "The fact that those making the investment decisions are primarily men can be one influencing factor," she says. Also, there has been previous academic research showing that fast-growth, high-tech entrepreneurs in the U.S. tend to be men, which is partly because women are less involved in science and engineering in general, says Kelly.

In all parts of the world, women entrepreneurs are more likely to run businesses that work directly with the consumer, like retail businesses, the GEM data shows. The data suggests women may choose these consumer-related businesses partly because they have lower aspirations for growth than men. Male entrepreneurs are more likely to gravitate toward capital-intensive manufacturing businesses and knowledge-intensive business services, the GEM data shows.

Even while more than 126 million female entrepreneurs were either starting or running new businesses in 2012 in the 67 countries measured, they are less confident about their abilities than men. In every economy studied, women reported lower perceptions of their entrepreneurial capabilities than men did, the report finds. Women in developed regions of Asia show the lowest levels of confidence in their abilities. Only 5 percent of women surveyed in Japan say they have the skills necessary to start their own business.

Meanwhile, perhaps surprisingly, women in sub-Saharan Africa showed much greater confidence in their entrepreneurship capabilities. Four out of five women in Zambia, Malawi, Ghana, Uganda and Nigeria say they have the skills necessary to start their own business. Part of the higher levels of confidence in sub-Saharan Africa is because almost 60 percent of women know other women entrepreneurs. Having direct interaction with a role model gives women confidence, says Kelly.

The entrepreneurship confidence levels in sub-Saharan Africa are also related to the types of businesses being started, says Kelly. "The typical business started by female entrepreneurs in these countries are often small, necessity-driven, consumer-oriented businesses with few or no employees and lower growth projections," says Kelly. "The perceptions about the skills needed for this type of business are different from those that involve more innovation, growth, and in industries with capital or knowledge intensity."

In every region, women report being more afraid of failure on average than their male counterparts, the report says. The fear of failure is linked to their lower rates of entrepreneurship because of the inherent risk of starting your own business. "When a woman has a choice between being an employee, especially when this is associated with an attractive salary, job stability, good benefits and even high social approval, she is taking a greater risk in entering entrepreneurship; she has to forego this opportunity in order to be an entrepreneur, and therefore has more to lose," says Kelly. Some of the most developed regions have the highest levels of fear of failure, including developed regions of Asia, Israel and Europe.

Read more: http://www.entrepreneur.com/article/227631#ixzz2dIef36Gq